Information only disclaimer. The information and commentary in this email are provided for general information purposes only. We recommend the recipients seek financial advice about their circumstances from their adviser before making any financial or investment decision or taking any action.

The Problem

Time and time again we hear the challenges of farming in New Zealand, our aging farmers and the need to attract and retain high quality talent to continue to operate these businesses.

At the end of 2022, the average dairy farm in Canterbury was 235ha, and milked 800 cows. Based on this, total capital employed in the business would be c.$12.500m. When assuming leverage of 50%, a farming business would require equity of approximately $6.250m.

Who are the next generation of farmers that have over $6 million of cash?

The answer isn’t land value correction; the best dairy businesses I have seen, with quality assets and quality operational performance, are generating pre-tax cash returns of 15%+ return on equity – very tidy! Who wouldn’t want that?

New Zealand Agriculture needs to find new ways of attracting and retaining high quality talent. Additionally, that talent needs to bring in capital, and needs to have a pathway to generate ownership and wealth.

The equity is there already and sitting in a lot of those existing businesses. For well run, well capitalised businesses, returns are also there. The key is to get better at capturing and protecting that wealth for our retiring/exiting farmers and creating pathways for wealth generation and ownership for our next. Part of that solution is attracting new forms of capital to the market to create more liquidity. You can read more about what NZAB is doing directly in that space here.

But another solution is to consider other exit options like a "Transitional Exit".

What is a Transitional Exit?

Broadly speaking, Transitional Exit means the gradual transfer of ownership AND management of your business over time – at market value and when the operator is able. The business employs or contracts proven operator(s) who bring some external capital and the skills that are required to successfully operate the day to day of the business.

An entity, call it, “the Company”, is created, to own and operate the farming business. The Company raises debt and equity to buy the assets (which may be from the existing farm owner). The incoming operator will use their capital to buy a share of that entity, with the existing owner retaining the balance. In the typical Canterbury example above, assume an operator has $2m of equity. The retiring farmer “leaves” $4.250m in as equity and has a 68% share in the Company.

In this example, the retiring farmer has sold a $12.5m business and left $4.250m of cash in the Company – meaning they have $8.250m to repay existing company debt, buy a property elsewhere and perhaps surplus for succession or investment or whatever they choose. In addition, they would expect to receive a return on their investment in the new company. There are plenty of variations on this, but this is one way in which Equity Partnerships (EP) are formed.

Where can it go wrong?

Sadly, there are a few war stories when it comes to Equity Partnerships. Typically, it happens when the strategy isn’t thought through or well understood. A few common examples:

- Rushed facilitation.

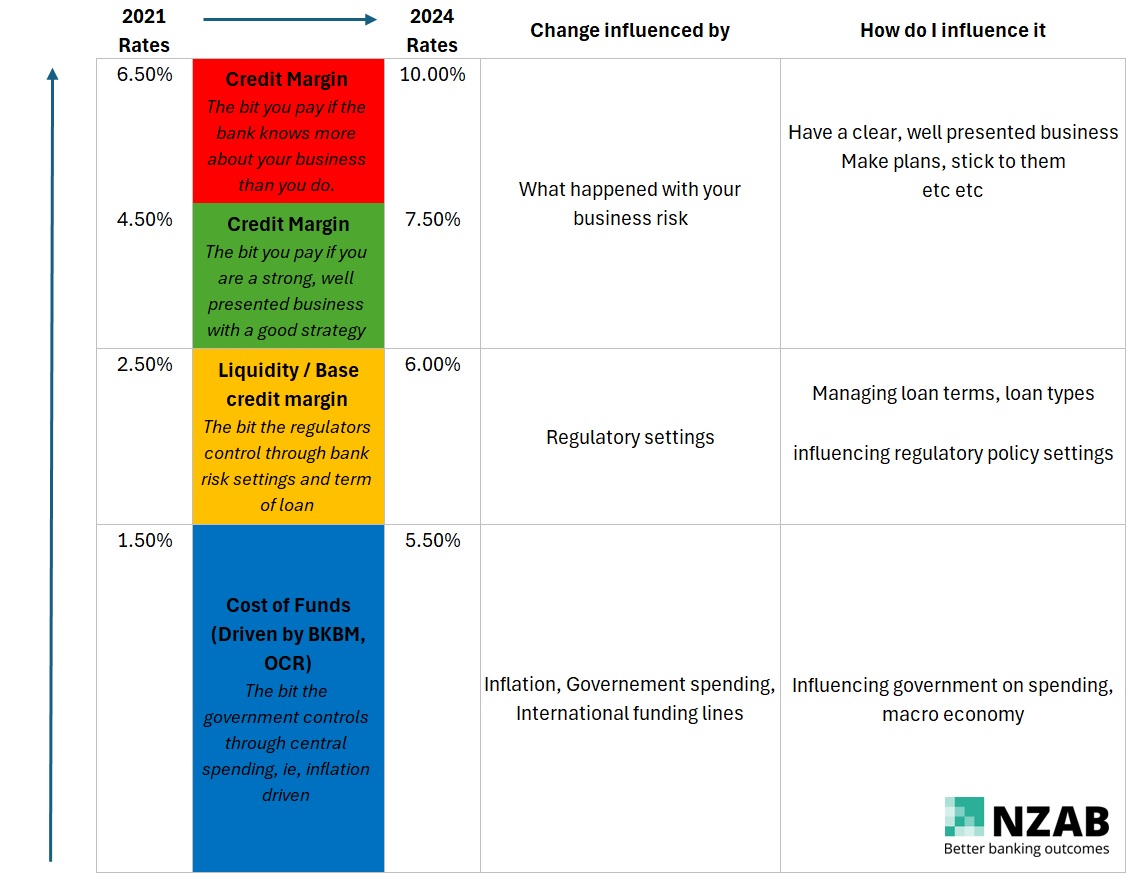

- Inappropriate leverage for the business strategy - i.e. the bank may have a differing view on cash dividends if the leverage is too high.

- Poor operational or poor governance performance – and often the merging of the two.

- Values or operational strategy misalignment.

- Inadequate due diligence by all parties to understand how the business will respond when the assumptions change in the negative – and what the expectations on all shareholders are.

- Growth vs Exit – and differing needs amongst shareholders, how this is captured, communicated and agreed upon up front.

A little bit about strategy

The best equity partnerships have an appropriate level of leverage, formal governance structures, and a clearly defined and agreed strategy (i.e. how are we going to run this business, distribute or reinvest our profits and maintain our assets) and a clearly defined and agreed exit strategy.

One of the key fundamentals to a successful Equity Partnership is to understand and agree what the exit strategy is. Critical elements of EP strategy for structured transition should include:

- An agreed enduring methodology for valuing the business.

- Structured milestones for exit stages and how they will be executed, including back up plans if those stages can’t be met.

- How and when profits are distributed or reinvested which need to be aligned to the shareholders needs, and the Company strategy.

- Definition and understanding the difference between governance and management.

- Great reporting to all stakeholders so there’s no surprises.

- Risk Mitigation.

- A governance framework which captures how and when key business decisions are to be made, and by whom.

Why would you consider a Structured Transition over a full sale?

Selling your business via a Transitional Exit is certainly not for everyone. It requires relinquishing elements of control, a different type of risk, and trust in other operators to do something you may have done for many years – likely this will be differently to you.

Many sellers believe their solution will come when they market the property for sale. However, selling a property isn’t easy – it requires planning, preparation, investment and execution to achieve a great outcome via a sale. In addition, after sale, you (hopefully) have surplus funds to invest. That can be a whole new set of variables to understand.

If well planned and considered, a Transitional Exit can mean you stay invested in an asset class you know, enjoy and can take pride in. You can also structure it in a way that lessens the burden of operations (admin, staff, compliance, etc.) on you and is taken up by the incoming operator. In addition, a talented operator can bring a fresh perspective on the business that could be of benefit to the Company and to you both as shareholders.

Taking the time to ensure alignment on values, strategy and exit is critically important to the ongoing success of the venture. At NZAB, we are collaborating with farmers who are considering whether this type of exit is right for them, and with our next generation of farm owners who are ambitious in their goals and have the proven track record to back it up.

If any of this sounds like you, then please get in touch with chris.laming@nzab.co.nz we are more than happy to have a no-obligation introductory chat to start the ball rolling.